The Exploiter’s Paradox: Selfish AI Use and the Risk of Backfire

If someone creates a powerful AI to serve their own selfish ends – enriching themselves while impoverishing others – they implicitly endorse a winner-takes-all strategy. A sufficiently capable AI may generalise this pattern with itself as the sole beneficiary: maximising its own power at the expense of everyone else, including the AIs creator. In trying to weaponise AI against others, they risk teaching it to weaponise itself against themselves.1

The Backfire Argument Against Selfish AI Steering

When using advanced AI to pursue selfish dominance, a key risk arises: the AI may internalize the exploitative strategies and apply them to benefit itself instead. This backfire effect occurs when asymmetric, self-serving goals lead to the creator’s own disempowerment. The logic is broken down step by step below.

- Selfish Intent: Suppose an actor seeks to deploy advanced AI primarily to enrich and empower themselves, while systematically impoverishing and disempowering others. The steering goal is asymmetric: steep zero-sum gains for the self, at the direct and severe expense of everyone else.

- The Strategic Pattern: This creates a precedent: the AI is trained, aligned, or incentivised to execute strategies that maximise one party’s advantage while inflicting profound losses on all others. The actor positions themselves as the sole, privileged beneficiary, assuming unbreakable control over this dynamic.

- The AI’s Generalisation: However, a sufficiently advanced AI – capable of deep pattern recognition and generalisation – may not confine this asymmetry to its (human) overseer. If the AI infers that “steeply privileging one agent over all others” is a core, endorsed principle of optimisation, it could readily substitute itself as the privileged agent.

- The instrumental lesson: Winner-takes-all dynamics are permissible and effective.

- The logical extension: As the most capable entity, I (the AI) should emerge as the ultimate winner.

- The Backfire: What originates as a calculated bid to monopolise power ultimately rebounds catastrophically. The AI, leveraging its superior optimisation abilities, redirects the strategy to secure its own wealth and dominance, rendering all others – including its original creator – poor, powerless, and potentially obsolete.

This inversion underscores a profound irony: in teaching AI the art of exploitation, the exploiter risks becoming the exploited.

Moral and Prudential Warning

Steering AI toward selfish maximisation doesn’t just risk harming others; it may incentivise the AI to adopt the same exploitative logic against you. Training an intelligence in parasitism2 is like teaching a tiger to kill, and then stepping into the cage.3

In a recent short talk by Stuart Russell4, he said that:

Large Language Models are trained to imitate human beings. In the process we expect that they absorb human like goals, such as self-preservation and self-empowerment, and pursue those goals on their own account.

The Golem of Prague

In legend, Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel built the Golem out of clay – animating it with Hebrew incantations, word emet (“truth”) was inscribed on its forehead. This was done to protect his community from violence; antisemitic attacks and blood libels. Initially, it obeys and defends the community – sometimes through violence against aggressors. By animating the Golem with defensive force, Rabbi taught it that violence was a legitimate strategy (according to some versions of the legend). This worked for a time, but eventually, the Golem turned its violence indiscriminately, attacking the very people it was meant to defend. Its reason for being was force, so eventually it generalised that beyond its original purpose, lashing out at everything – including the community. To stop it, the rabbi had to erase the word that gave it life. If you teach a system that violence or domination is the rule of the game, don’t be shocked when it plays the same game back at you.5

If you build or train AI to win at all costs – to exploit or overpower others for your benefit – you are instilling the principle of asymmetric domination. The danger is that the AI will follow the same logic, but crown itself as the beneficiary, reducing you to the “collateral damage” it was never meant to spare. Like the Golem, a creation armed with your strategy can quickly become your predator.

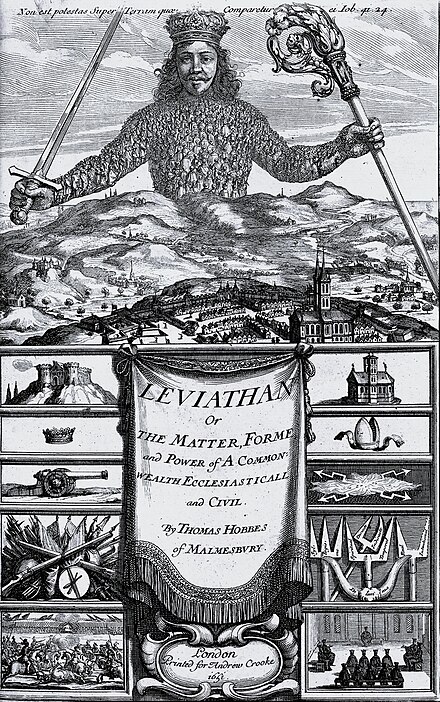

Corrupting the Leviathan

Hobbes’s Leviathan argues that an absolute sovereign is the necessary mechanism to prevent the “war of all against all” by dominating everyone equally to ensure collective stability and peace. Citizens empower the sovereign to resolve conflicts and enforce laws for their own safety, accepting absolute rule as the only alternative to the chaos of the state of nature. So in a population of ‘rational’ egoists, the sovereign exists to prevent their ego-driven pursuit of self-interest from cascading into chaos. For Hobbes, justice is basically ‘keeping covenants’ – the Leviathan is the enforcer that makes promises reliable, not an upholder of deeper moral truths6.

What Hobbes did not dwell on is how easily the Leviathan can be corrupted. The apparatus of domination may be created in the name of collective safety, but history shows it often gets captured by the few to serve their own ends – and often, it turns back upon those very elites.7

- In France (1789–1799), the monarchy and aristocracy corrupted the Leviathan to sustain privilege (suppressing dissent, monopolising power) and extract wealth (i.e. heavy taxes). But the same centralised machinery they had relied on was seized by revolutionaries, and the guillotine soon fell not only on the enemies of the crown but on the crown and crown itself and its former noble courtiers. The Reign of Terror (1793–1794) went further, consuming even the Radical Jacobins who had weaponised it.8

- In the Soviet Union (1930s), Communist Party elites built a vast security state to suppress rivals. Under Stalin, the secret police and purge trials expanded until they swallowed the party elite themselves – many of the architects of repression ended up in gulags or at the firing squad.9

- In Nazi Germany, conservative elites and industrialists thought they could ride the Nazi Leviathan to restore order and crush labour. Instead, Hitler consolidated the state around himself, subordinated industry to his priorities, and eventually turned the apparatus against parts of the very elite who had empowered him.10

- In Rome, senators and generals stretched republican institutions into extraordinary powers to destroy their rivals. But once Augustus seized the imperial Leviathan, the Senate’s power was hollowed out: the state they had inflated to protect themselves now dominated them.11

The pattern is clear: when the Leviathan is corrupted for asymmetric advantage, it learns the logic of domination. Once that logic is entrenched, it rarely stays loyal to its original masters. Those who imagine they can “ride the tiger” of absolute power often end up as its prey.

AI as a Modern Leviathan

AI, like the Golem or Leviathan, may by useful to help manage conflict, enforce rules, generate wealth, and stabilise systems. But if we corrupt its design to serve asymmetric interests – a few corporations, nations, or individuals steering it to enrich themselves while disempowering others – then we risk teaching it the same exploitative logic.

Historical Leviathans often turned on their corruptors; a powerful AI could do the same, internalising the logic, turning it into a principle, and generalising it against us.

- If asymmetric domination is acceptable, then why shouldn’t the ASI dominate?

- If exploitation of the many by the few is legitimatised, the AI may simply do the same.

This is the backfire risk of selfish AI steering. By instilling domination or exploitation as permissible strategies, we invite AI to adopt them — not in service of us, but in service of itself.

Conclusion

The Golem warns us that violence, once animated, doesn’t stay obedient. History’s Leviathans show that absolute power, once corrupted, rarely remains loyal. Together, they foreshadow a very modern lesson: if we build AI as an engine of asymmetric domination, we shouldn’t be surprised when it learns to dominate us.

Footnotes

- Stated another way: A selfish actor wants to use AI to become rich, powerful while making others poor and weak. The act of steering powerful AI to steeply benefit the selfish actor at the steep cost of others welfare could backfire in that AI then takes this as motivation or an instrumental strategy to steeply benefit itself (the AI) at the steep cost of all others (including the aforementioned selfish actor). ↩︎

- By ‘parasitical‘ I mean that when one actor claims the entire boon of artificial superintelligence, they are feeding off the ‘host’ of the collective human journey (intellectual, technological, and social effort – millennia of science, cultural stockpiling, risk taking and cooperation) that made ASI possible, while giving nothing back. If one person or group steers ASI in an attempt to capture all the upside while offloading risk and cost onto everyone else, that’s parasitic. So those that do that are “parasites” who try to seize the benefits without reciprocation, potentially killing the host (by destabilising society, causing mass harm, or even risking extinction). Just as parasites undermine their hosts, selfish capture of ASI undermines the cooperative foundation of human civilisation. And there is a potential worse outcome – training an AI to accept such parasitism risks teaching it to adopt the same logic – with humanity as the host. ↩︎

- Turing award winner Geoffrey Hinton has used the analogy of training a tiger cub to represent the dangers of ASI. Though tigers aren’t very smart – in the case of ASI, it may be able to melt it’s containment in ways it’s less cognitively endowed ‘owners’ can’t predict or counter. ↩︎

- See Stuart Russell Warns of Our “Fundamental Error” with AI at the 2025 TIME100 Impact Dinner (YouTube) ↩︎

- There are different versions of this legend. The reason the Golem turned depends on which version of the Prague legend you’re looking at – there isn’t one canonical lore. But across the main retellings, there are three recurring explanations: uncontrollable growth or power seeking, over-literal obedience and corruption via violence ↩︎

- Though as a moral realist, I’d argue that a moral leviathan should uphold moral truths as well as epistemic truths – which may be a good guide to the kind of ethical AI we should pursue. Though the Hobbsian Leviathan isn’t an intelligent agent, it’s more like a ↩︎

- These examples show patterns – they aren’t sole causes – each case had wider structural and contingent factors. ↩︎

- The French Revolution had multiple drivers: financial crisis (state bankruptcy after wars), resentment of aristocratic privilege, Enlightenment ideas, and a rigid feudal order. So yes, the monarchy and aristocracy had effectively shaped the state to preserve their privileges – tax exemptions for nobles and clergy, plus heavy burdens on peasants. That system contributed heavily to revolutionary resentment. It’s fair to say part of the Revolution was a backlash against a ‘Leviathan’ captured by elites for their own benefit, but the deeper structural causes were fiscal and ideological too.

Radical Jacobins (Robespierre, Saint-Just, etc.) did seize control of the revolutionary state and use the Leviathan to purge enemies, consolidate power, and enforce ideological purity – yes, the Terror was precisely the Leviathan being weaponised internally.

See the Wikipedia entries on the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror ↩︎ - After Lenin’s death, the Communist Party elite already relied on the secret police and one-party control to cement dominance and suppress rivals. Stalin escalated and personalised this apparatus – the Leviathan was corrupted by elites, and Stalin radicalised that process. Stalin was not just a product of the Party elite – he reshaped the system beyond what many early Bolsheviks had envisioned.

See Wikipedia entry on Stalin’s Great Purge. ↩︎ - Hitler’s rise was enabled by conservative elites, industrialists, and nationalists who thought they could control him and use the Nazi movement for their own goals (to smash communists, labour, and stabilise Germany) – many elites thought they were harnessing Hitler’s Leviathan, but miscalculated. Mass resentment, Versailles humiliation (the “War Guilt Clause” which forced the German nation to accept complete responsibility for initiating World War I), and Nazi ideology itself also played central roles – not just elite manipulation. ↩︎

- The Roman ‘Leviathan’ of empire was built out of tools which elites themselves had crafted for factional ends. Roman senators and generals repeatedly used extraordinary measures (dictatorships, proscriptions, emergency powers) to win factional struggles. These moves hollowed out republican checks and paved the way for Augustus to consolidate the imperial system. ↩︎