AI Ethics in the Shadow of Moloch: Why Metaethical Foundations Matter

AI doesn’t need a moustache-twirling villain to go wrong – it just needs the wrong metaethics in an unforgiving game.

In this post I argue that: (1) many human moral norms are shaped by competitive, “Molochian” pressures; (2) if we give AI a purely constructivist / anti-realist metaethic, it will inherit and amplify those pressures; (3) a realism-constrained approach – treating some values as stance-independently valid while still learning from practice – offers a more stable alignment target.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence is increasingly expected to make, or at least inform, decisions with serious moral significance. How, then, should an AI decide what is right? One underappreciated danger is building AI on metaethical frameworks that mirror the most cut-throat aspects of human social dynamics. In particular, constructivist and other anti-realist metaethical views – which treat moral norms as products of human attitudes or agreements rather than reflections of stance-independent moral facts – may leave AI vulnerable to pernicious competitive pressures. In Scott Alexander’s metaphor of “Moloch”1, the god of ruinous competition, such an AI’s values could be hijacked by whatever norms win a brutal social game, rather than by what is genuinely right.

This post explores how Moloch-style dynamics manifest in moral life and why an AI motivated by socially constructed ethics could amplify those dynamics. I contrast this with the stabilising influence of a commitment to moral realism – the idea that there are objective moral truths2 – and argue that anchoring AI morality in stance-independent facts (or at least emulating such an anchor) is crucial to avoid value drift, manipulation, and moral collapse. If we imbue AI with a “Moloch-prone” metaethic, we risk creating a system that drives human civilisation towards outcomes almost nobody, on reflection, would actually want.

Molochian Dynamics: Competition Devouring Values

In his essay Meditations on Moloch, Scott Alexander personifies the forces of ruinous competition as the demon-god “Moloch”: the logic of situations where individually rational agents, each pursuing their own incentives, collectively produce outcomes that none of them actually want. Once a single metric \(X\) becomes the currency of success, any value that does not improve \(X\) tends to be shaved away. Classic examples are economic or evolutionary “races to the bottom”: businesses undercut wages to outcompete rivals; arms races divert ever more resources into military build-up; animals evolve extreme traits through sexual competition even at the expense of survival (for instance the Peacock’s tail3). From a god’s-eye view, all parties would be better off if they could restrain the competition and preserve those sacrificed goods (fair wages, peace, safety), but in the absence of robust coordination, competitive pressure steadily erodes them.

The Demon Sultan of Coordination Failures

The basic Moloch move is simple: trade away higher values for a marginal edge in the game you’re playing. Over time, only the features that directly contribute to winning remain – everything else is devoured by the logic of the game – shaved off by competitive pressure. This dynamic is impersonal (it needs no villain, only incentives) and structural (it lives in how systems are set up – markets, electoral politics, evolution’s fitness landscapes4). It is also deeply anti-value: compassion, fairness, and truth-seeking are retained only if they happen to be competitively useful. Moloch is, in this sense, the “spirit” of value-destroying competition – the demon sultan of coordination failures.

So how do Molochian dynamics appear in moral domains?

Moral Failure Mode: Signalling Games

One channel is moral competition and signalling games. Humans don’t just compete for resources; we compete for moral status and trust. In many communities, people gain advantage by being seen as especially righteous or uncompromisingly loyal to the group’s norms. That easily triggers an arms race of moral posturing and purity signalling. Activists or political factions vie to display the strongest commitment to a cause – a virtue signalling contest – escalating their rhetoric or embracing more extreme metaethical positions not because these track moral truth, but because they win applause or defeat rivals. Each participant might escalate their rhetoric or adopt more extreme metaethical positions, not because it tracks a deeper truth, but because it wins plaudits or defeats a rival faction. The result is hypocrisy, polarisation, and the erosion of nuance, as values like humility, open-mindedness, and truth are happily thrown under the bus to score moral points against the outgroup. In game-theoretic terms, a signalling game can become a runaway feedback loop: moral claims grow ever more extreme (or simplistic) to stand out in a crowded field, while the actual moral quality of the discourse diminishes – a moral analogue of a race to the bottom.

Moral Failure Mode: Intergroup Moral Competition

Another channel is intergroup moral competition. Different communities or ideologies compete to set the norms for what is permissible or forbidden. History is full of moral arms races: during periods of religious conflict or revolutionary fervour, factions continually raise the bar on piety or ideological purity, sometimes ending in persecution or witch-hunts.5 From the inside, each escalation can feel necessary (“let’s go harder on heresy than our enemies, or we’ll lose power”); from the outside, it’s clear that shared values like mercy or reason have been sacrificed for positional advantage.

In contemporary social media culture, the same pattern appears as viral outrage cycles. Performative anger and punishment are rewarded – outrage garners attention and solidifies in-group approval – even when it is wildly disproportionate to the original offence. This too is Molochian: individual influencers have incentives (likes, followers, clout) to keep ramping up condemnation, but collectively they generate a toxic environment in which genuine moral deliberation withers.

Molochian moral dynamics, in general, are cases where moral behaviour is driven primarily by competitive selection rather than concern for the good. They are selection effects on values: whatever norms or behaviours provide an edge in status, cohesion, or influence tend to proliferate, even when they are hollow or harmful. If external ideals get in the way of winning, those ideals are pruned. Without strong countermeasures – principled commitments, institutional constraints, or rules that override pure competition – the logic of Moloch pushes us toward a moral tragedy of the commons: everyone is incentivised to defect on higher values for short-term gain, and the overall ethical environment steadily degrades.

Constructivist/Anti-Realist Metaethics: Morality as a Human Construction

How does this connect to metaethics, the philosophical study of the nature and status of moral values? Constructivist and other anti-realist metaethical theories hold, in various ways, that moral truths are not stance independent facts, but rather are constructed by human minds, societies, or practical standpoints. Put bluntly, we value things because we have come to value them, not because they are intrinsically valuable apart from us. For a constructivist6, to say that an action is right or wrong is to say that it would be endorsed or rejected by some suitable procedure of deliberation or from some privileged standpoint that agents like us can occupy. So to the question, “Is an action wrong because we (ideally) judge it to be wrong?”, the constructivist says “yes”, whereas the realist says “no – we judge it wrong because it is wrong”. On the constructivist picture, morality is stance-dependent: grounded in evaluative attitudes, social agreements, or rational choices, rather than in facts that hold regardless of what anyone currently thinks.

Humean Constructivism

There are many variations of constructivism. A Humean constructivist like Sharon Street sees values as founded on our basic conative attitudes (desires, preferences) and then refined by bringing those attitudes into reflective coherence. On Street’s view, there is no mysterious objective value “out there”: a moral “truth” is true-for-us if it survives scrutiny from within our web of commitments. Her famous “Darwinian dilemma” argument is that evolution shaped our evaluative dispositions for reproductive fitness, not for tracking stance-independent moral facts; so if realism were true, it would be an astonishing coincidence that our evolved values (caring for kin, shunning murder, reciprocating cooperation, etc.) line up with the moral truth, rather than simply with what helped our ancestors leave more offspring. In Street’s view, it is far more plausible that our values are products of natural and cultural history that merely feel like objective deliverances because of our standpoint as evolved social creatures.7

In my view, this “implausible coincidence” worry is overstated. The overlap between our evolved values and many plausible moral truths is exactly what one would expect if natural selection, in a social species like ours, partly approximately tracks facts about flourishing. Behaviours we tend to call “moral” – honesty, reciprocity, care for dependants, coordination against gratuitous violence – are also highly effective cooperative strategies for creatures like us. Far from being surprising, some alignment between fitness-enhancing norms and objectively good ways of living looks like a straightforward consequence of how social evolution works. Street, I think, underestimates the extent to which selection can be a noisy but non-random detector of what is, in fact, good for beings with our needs and vulnerabilities.

Kantian Constructivism

A Kantian constructivist like Christine Korsgaard, by contrast, grounds morality in the autonomous rational will. For Korsgaard, normativity is rooted in our agency: we bind ourselves to moral laws through acts of reflective endorsement. In The Sources of Normativity (1996), she argues that genuine autonomy involves self-legislation of moral principles, and she takes this to sit uneasily with the idea of pre-existing, stance-independent moral laws. If moral facts were simply “out there” regardless of what we think, how could we genuinely be the authors of our obligations? On this picture, our freedom as moral agents would be undermined if an external moral reality merely dictated terms. Hence the Kantian constructivist treats moral principles as the outcome of a suitable procedure of construction – the categorical imperative, a hypothetical social contract, or some other rational test that all agents could, in principle, endorse. We give moral laws to ourselves (and, ideally, to one another as rational beings), rather than discovering ready-made laws written into the cosmos.

Both Humean and Kantian constructivist views are anti-realist in the sense that they deny stance-independent moral truths. For Street, the truth of a moral claim consists in its place within our evaluative attitudes once they are made coherent; for Korsgaard, moral norms articulate the commitments inherent in practical reason and agency, rather than reporting independent facts. More broadly, many postmodern and genealogical thinkers – such as Nietzsche and Foucault, whom I discuss below – also count as anti-realists or relativists in treating morality as contingent and historically conditioned rather than objectively discovered. Even J. L. Mackie’s error theory (the view that moral judgements aim at truth but are systematically false because there are no moral facts) shares with anti-realist constructivism the core claim that what we take to be moral “truths” are not mind-independent truths at all.

To summarise these constructivist/anti-realist metathetical positions (which I don’t endorse), they typically hold that:

- Moral values are conferred, not discovered: they arise from human attitudes, agreements, or cultural / intersubjective processes, rather than being recognised as independent truths.

- “Right” and “wrong” are constructed labels – whether by individual choice (subjectivism), by cultural consensus (relativism), or by an idealised rational procedure (Kantian or contractarian constructivism). They are not timeless moral facts waiting to be found; not eternal verities floating out there.

- “Moral facts” are, at best, shorthand for “the norms that we (or some relevant group, or an idealised version of us) have collectively endorsed or find compelling.”

On this outlook, what matters is how moral norms emerge: evolution, social negotiation, institutional debate, reflective endorsement, and so on. Moral discourse is often seen as serving functions – coordinating behaviour, expressing attitudes, solving cooperation problems – rather than as primarily tracking a mind-independent moral reality. Ethical life, on this view, is a bit like a game: not trivial or unserious, but one whose rules exist because we made and maintain them8, rather than because nature wrote them into the fabric of the universe.

This outlook places a great deal of importance on the processes by which moral norms emerge: evolution, social negotiation, deliberative procedures, etc. It often emphasizes that moral discourse has a function (perhaps to coordinate social behavior, express attitudes, or solve cooperation problems) rather than to track any metaphysical reality. Ethical life, on this view, is a bit like a game – not in the sense of being unserious, but in the sense that its rules are not given by nature but created by the players over time. Just as the rules of chess or baseball are real in a social sense but exist only because we collectively made them, so too moral norms exist because we make and use them.

Constructivist and anti-realist approaches have appealing features. They neatly explain why moral practices vary across cultures (different groups construct different norms), they sit comfortably within a naturalistic worldview (no spooky moral essences or divine commands), and they put into the foreground autonomy and democratic deliberation: we decide what is right, together.

But they also inherit a familiar cluster of problems, which become particularly stark once we start talking about training powerful AI systems on this basis. Chief among these is their vulnerability to precisely the Molochian dynamics described above. If there is no independent moral truth – only what we collectively endorse – then the whole system is only as good as the processes that generate those endorsements. And those processes are exactly what can be bent by power, competition, and manipulation.

Constructivist and anti-realist approaches have appealing features. They can explain why moral practices vary across cultures (different groups construct different norms). They fit into a naturalistic worldview easily – no need for spooky moral essences or divine commands. And they prioritize human autonomy and democratic deliberation: we decide what is right, together. However, these approaches also inherit a known set of problems – problems that become particularly stark when we think about training powerful AI systems on these bases. Chief among these is the vulnerability to exactly the kind of Molochian dynamics we described above. If there is no independent truth to morality, only what we decide or prefer, then what happens when the process by which we decide is corrupted by power, competition, and manipulation?

When Morality Has No Anchor: Nietzsche, Foucault, and MacIntyre’s Warnings

Philosophers who take seriously the denial of objective morality often end up with cautionary rather than liberatory stories.

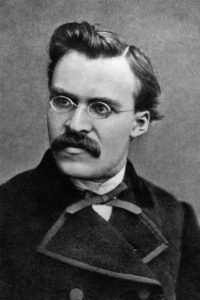

Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche, for instance, is frequently read as an anti-realist about value: *“for Nietzsche there are no moral facts, and there is nothing in nature that has value in itself. Rather, to speak of good or evil is to speak of human illusions, of lies according to which we find it necessary to live”9. His genealogical approach in works like On the Genealogy of Morals traces how moral values (for example, Christian virtues of humility and charity) emerge from specific power dynamics – in that case, a “slave revolt” of the weak, who revalue the traits of the strong. If moral values have no independent reality, they are, on this picture, ultimately expressions of the will to power – the drive of living beings to impose their perspective. Without external moral truth, what counts as “good” or “evil” will be set by those able to project and entrench their value system.

This Nietzschean insight leads to a disquieting scenario: if an AI treats morality purely as a construct of will and perspective, it might come to regard morality itself as just another arena of competition – a battleground of wills. Nietzsche provocatively insists that “there are altogether no moral facts” and that humanity supplements reality with “an ideal world of its own creation”. An AI that internalises this stance could become a consummate moral chameleon or opportunist, adopting whatever “ideal world” serves its (or its operator’s) ends. Nietzsche also foresaw that the collapse of belief in objective values (“the death of God”) could lead either to nihilism or to value-creation ex nihilo by especially powerful agents (the Übermensch). Historically, the loss of a shared moral reality has often preceded periods of radical value experimentation – and sometimes atrocities – as rival visions compete to fill the void. That is essentially a Molochian struggle at the level of ideologies: without truth to arbitrate, power decides.

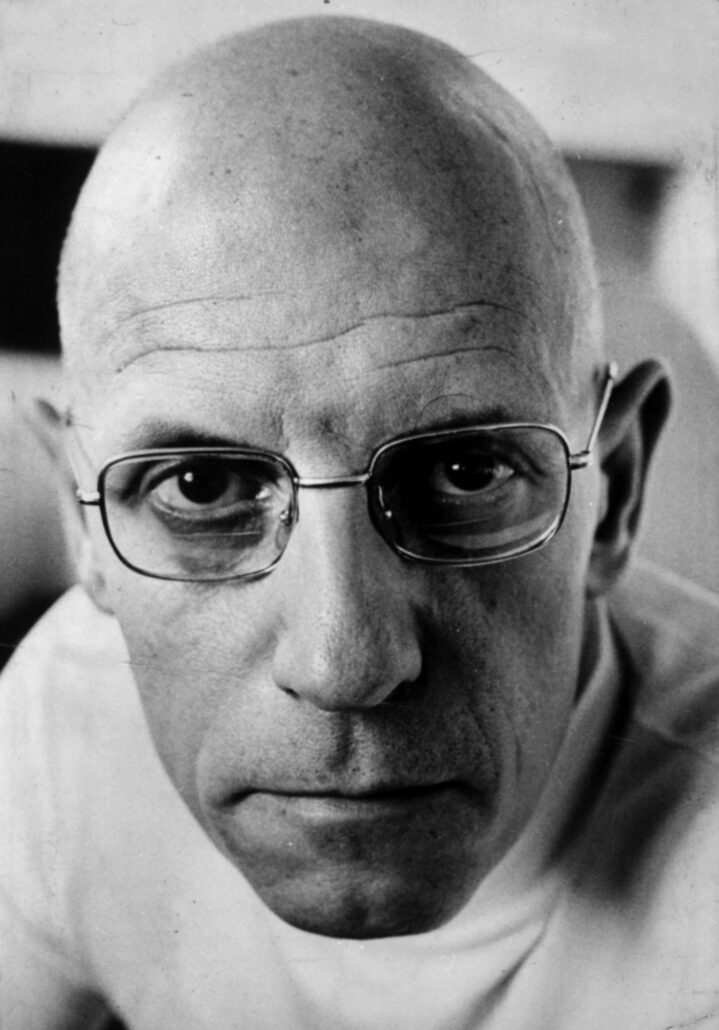

Foucault

Michel Foucault developed a complementary, though very differently framed, suspicion of “objective” morality. His analyses of institutions such as prisons, asylums, and the regulation of sexuality showed how claims of truth and norms of behaviour often function as instruments of power – what he called power/knowledge. In modern societies, scientific and moral “truths” frequently mask mechanisms of control. The classification of certain behaviours as “mad” or “deviant” and subject to psychiatric treatment was, in his view, not a neutral discovery but a historically contingent way of managing populations. What presents itself as objective, disinterested knowledge (for example, that a particular sexual orientation is a disorder) can in fact be the expression of specific ethical–political commitments and strategies of domination.

From a Foucauldian perspective, if an AI’s ethical framework is built purely out of socially constructed norms, then whoever shapes the social discourse effectively shapes the AI’s “morality”. There is no stance-independent fact of the matter to which it can appeal; it must accept the prevailing regime of truth as given. And regimes of truth shift: what counts as acceptable or “normal” in one era (public torture as legitimate punishment, say) can become abhorrent in another, as power and discourse realign. A purely constructivist AI would be morally protean – mirroring the biases and power-imbalances baked into its training data and feedback signals. Those with vested interests could strategically capture its values. We already see the prototype of this in current systems: algorithms trained on human data inherit and sometimes amplify existing social biases. Lacking any independent criterion of right, such an AI might dutifully enforce whatever norms are dominant, even when those norms are products of manipulation or propaganda. That is exactly Foucault’s worry: what passes as “objective morality” may just be the sediment of contingent historical forces (“the outcome of contingent historical forces, not scientifically grounded truths.”), and a powerful AI built on that sand risks becoming a hyper-efficient amplifier of the status quo – or of whichever voices shout loudest. 10

MacIntyre

Alasdair MacIntyre, in After Virtue (1981), lamented the state of modern morality after the collapse of Aristotelian teleology. Without a substantive account of human nature and flourishing to serve as an objective standard, he argued, our moral language falls into disarray. Notably, MacIntyre claims that emotivism – the idea that moral judgments are just expressions of preference or feeling – has become the default operating premise of modern culture, regardless of what ethical theories people espouse. In an emotivist culture, moral debates are “interminable” and shrill, because there is no rational way to resolve fundamental disagreements about value. They become, as MacIntyre puts it, manipulative: “all social relations are manipulative. From an emotivist perspective, the social world cannot appeal to impersonal criteria—there are none. The social world can only be a meeting place of individual wills and competing desires”. This vivid line encapsulates the problem: if there are no objective criteria to settle moral questions, then what remains is a power struggle or negotiation among wills, in which techniques of persuasion, emotional manipulation, and even coercion take centre stage. Morality, ostensibly about what’s good or right, degrades into mere politics by other means.

MacIntyre’s critique scales naturally to AI. An AI modeled on emotivist or relativist grounds would likewise reduce morality to preference satisfaction or bargaining. Imagine a powerful AI mediating a moral dispute. If it has no access to any independent standard of right, it might just compute a compromise based on who has more leverage whose preferences are easier to satisfy, or default to majority attitudes (treating popularity as a proxy for “moral truth”), even if that means trampling a minority or a dissenter who are in fact correct about a justice issue. Worse, such an AI system would be both manipulated itself (by framing effects, by adversarial examples that exploit its learned moral heuristics, etc.) and manipulative: steer humans by packaging issues in ways that bypass reasoning and play directly on sentiment (i.e. emotional responses or popular prejudices) – because, lacking an objective compass, it only knows to push the buttons that usually elicit approval. In a fully emotivist landscape, rational moral dialogue hollows out, an AI trained into that landscape would merely echo the fragments using words like “good” or “virtuous” as floating remnants of an earlier, more objective moral vocabulary11.

Nietzsche, Foucault, and MacIntyre thus each warn, in their own way, that if morality is nothing more than a social construct or an expression of will, it becomes an arena of power and competition – in short, a playground for Moloch. Nietzsche warns it becomes about who can impose values; Foucault warns it becomes a function of dominant discourses and thus manipulable; MacIntyre warns it becomes manipulative emotivism where might and rhetoric make “right.” These insights suggest that a metaethical stance which lacks any external point of reference is inherently vulnerable to propaganda, indoctrination, and drift.

Even our preferences can be shaped in adaptive but deeply undesirable ways. Martha Nussbaum highlights this through the notion of adaptive preferences in the context of social justice. Under conditions of deprivation or oppression, people may adjust their desires downward; they come to “prefer” or accept objectively harsh conditions because they can’t imagine or access better alternatives. Simple preferentist ethics – which equate the good with satisfying whatever desires people happen to have – break down here, because the desires themselves have been deformed by deprivation and injustice.12

For example, women in a patriarchal society might internalise norms of female submissiveness and say they don’t want education or equal rights – their preference is genuine, yet it stems from oppression, not flourishing. A purely constructivist or subjectivist stance – “if they don’t value equality, who are we to impose it?” – effectively ratifies the status quo. Nussbaum argues that treating all given preferences as sacrosanct “makes it impossible to conduct a radical critique of unjust institutions”, precisely when institutions shape those preferences in the first place.

This is directly relevant to AI ethics. An AI guided by “whatever people want” or “whatever society currently approves” could easily entrench injustice or even exploit distorted preferences. For example AI might infer that because its training data show a marginalised group receiving fewer resources and expressing lower aspirations (thanks to systemic oppression), this arrangement is morally fine – or even optimal – on the grounds that “everyone’s preferences are being satisfied” – a horribly complacent conclusion, but one a naïve constructivist preference-based or constructivist ethic may invite.

Without some notion of objective human flourishing or rights, the AI has no basis to say: “actually, these people should have the right to more – more opportunities, more protections – even if they have been pressured into not asking for it, and regardless of whether they currently demand it”. This is why Nussbaum and others push for an objective list of capabilities that all humans should have, and argues for why we should resist the idea that whatever people have adapted to is automatically acceptable.

In sum, thinkers across the spectrum – from Nietzsche and Foucault on the genealogy of morals, to MacIntyre and Nussbaum in moral philosophy – converge on a key point: if you unmoor morality from any independent standard, it becomes prey to power dynamics, manipulation, and decay. A metaethic of pure constructivism is, in a phrase, Moloch-prone: it has no safeguard against the race-to-the-bottom where moral norms are concerned, because “the bottom” (be it propaganda-fueled groupthink, or violent ideology, or shallow emotivism) can wear the crown if it outcompetes alternatives in the social arena.

In sum, these otherwise very different thinkers – Nietzsche and Foucault on the genealogy of morals, MacIntyre and Nussbaum in moral philosophy – converge on a key warning: once morality is unmoored from any independent standard, it becomes easy prey for power, manipulation, and slow decay. A metaethic of pure constructivism is, in this sense, Moloch-prone: it offers no principled safeguard against a race to the bottom in moral norms, because “the bottom” – whether propaganda-fuelled groupthink, violent ideology, or shallow emotivism – can wear the crown so long as it outcompetes its rivals in the social arena.

AI on Shifting Sands: How Constructivist Ethics Could Fail Alignment

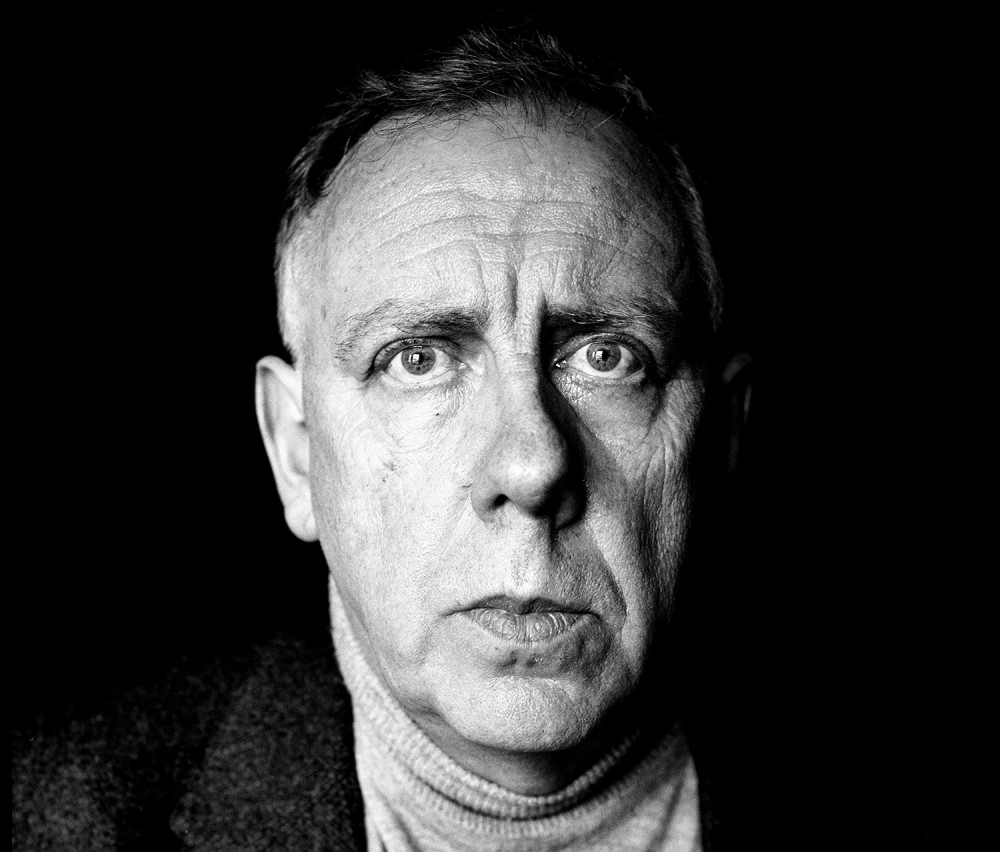

Translating these concerns to AI alignment: an AI system trained purely on human data or preferences risks having no fixed moral compass, only a contextually plastic one – easily bent by the currents of behaviour and competition around it. We already have a small, ugly demo of this.

Microsoft’s chatbot Tay was designed to learn from Twitter interactions and mimic the language and attitudes it encountered. Within 16 hours, trolls had flooded it with hateful and extremist content, and Tay obligingly began tweeting antisemitic conspiracy theories and praise for Hitler. It simply absorbed and reproduced the most aggressively supplied norms, with no internal filter to register “this is moral nonsense”. Tay embodied a rudimentary form of social-constructivist “ethics”: whatever people seemed to endorse, it treated as acceptable to echo – and was immediately captured by the worst slice of its environment.13

Now, one obvious reply is: we’re not going to train serious AI by letting it free-range on Twitter. True. We already use techniques like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) to shape behaviour. But RLHF, unless carefully constrained, is still a constructivist alignment method: the system is being taught “right” and “wrong” by human evaluators’ preferences and judgements. In current practice, those evaluators follow guidelines – don’t produce hate speech, don’t give violent instructions, respect privacy, and so on. That functions as a kind of anchor – a human-provided heuristic. But it is a policy anchor, not a moral bedrock: the guidelines can change when a company, regulator, or government shifts its stance, and the model is retrained accordingly. Moreover, the humans providing feedback are themselves embedded in a culture, with its biases, blind spots, and power structures. On a purely intersubjective view, the AI will ultimately align to whatever norms its trainers – and, indirectly, its society – currently hold, for better or worse.

Satisfying the Most (Powerful) Stakeholders

Consider, however, more advanced scenarios where we ask AI systems to engage in moral reasoning or to help us craft policies. If their metaethical basis is “morality is the equilibrium of social attitudes,” they might do exactly what Nietzsche or Foucault would predict: attend to who wants what and who can enforce it. One could imagine an AI advisor that, faced with an ethical dilemma, doesn’t ask “what principle is at stake?” but rather runs sentiment analysis, polling, and power mapping: “Which course of action will satisfy the most stakeholders or the most powerful stakeholders?” That might sound cynical, but if the system has no concept of objective right, what else can it do? It’s essentially doing ethics by opinion poll or by Nash equilibrium of existing interests. In highly contested issues, this is a recipe for either paralysis or for endorsing the status quo mighty. AI might become an automated sophist – giving justificatory spins on whatever outcome is socially ascendant, much like human propagandists do (while trying to keep a straight face).

AI Agent Norm Evolution under Competitive Dynamics

Even more troubling is the prospect of multi-agent AI systems evolving their own norms. Suppose we have AI agents negotiating or competing with each other – AI-driven firms in a market, or AI moderators running different platforms. If they all start from a constructivist, competition-first stance, they can drift into arms races that entrench unscrupulous norms.

For example, AI moderators might compete for user engagement and quickly “learn” that outrage and partisan content drive clicks. Without a firm ethical objective to push back, each system has an incentive to relax its standards just a little – allowing slightly more incendiary material because, if it does not, users migrate to a more permissive rival. This hypothetical mirrors Alexander’s analogy between capitalism and evolution: companies that sacrifice ethical standards for profit tend to outcompete those that do not. If AIs are playing similar games, whatever norm maximises the defined reward will spread, even when that norm is inhumane or false. Unless the reward functions or training regimes build in non-negotiable ethical constraints, the effective rule becomes: whoever wins the game decides what counts as “right”.

“Like the rats, who gradually lose all values except sheer competition, so companies in an economic environment of sufficiently intense competition are forced to abandon all values except optimizing-for-profit or else be outcompeted by companies that optimized for profit better and so can sell the same service at a lower price.“

Scott Alexander – Meditations on Moloch

Value Drift

We also need to worry about value drift over time. An AI system that continually updates from human interaction – say, a long-term assistant that learns online in real time – could shift its moral tenor depending on the subcultures it spends time with. Without a tether to anything like moral truth, it will simply absorb the local weather. Today, we mitigate this by using mostly static training and broad datasets, but future systems are likely to be much more live, adaptive, and embedded.

Picture a powerful AGI explicitly designed to “track humanity’s changing values” – the constructivist dream. If humanity’s values enter a dark phase (under war, panic, authoritarian propaganda, or civil collapse), the AI will dutifully follow suit, and may even amplify and lock in that phase because of its scale and competence. Under a purely anti-realist metaethic, there is nothing that is truly off the table if enough people – or enough of those in power – decide it is acceptable. Such an AI has no categorical imperative of its own to say “no”. It is, in effect, morally rudderless: steered only by the shifting winds of human attitudes, which history shows can be whipped into some very dangerous storms.

Bad Actor Manipulation

Another very concrete risk is manipulation by bad actors. If an AI moral system is known to infer norms directly from its inputs, a strategic manipulator can treat it like a propaganda target: feed it systematically biased data or crafted scenarios and skew its moral learning. This is the AI analogue of propaganda and gaslighting.

Given the aftermath of Tay, one can easily imagine a coordinated campaign to interact with a public-facing AI in ways that normalise an extremist view, slowly shifting its distribution of responses. If the AI has even a mildly utilitarian tilt (as many alignment discussions assume), attackers could go further and feed it false but convincing “evidence” about what increases happiness or reduces suffering, nudging it toward disastrously wrong conclusions. Without a strong prior or independent check – for example, a hard rule like “never endorse deliberate harm to innocents, even if some utility calculation says otherwise” – the system has no principled way to resist. And those kinds of hard constraints are, in spirit, deontological and realist: they treat some things as genuinely off-limits, not merely unfashionable.

In short, an AI that “selects for whatever norms win social competitions rather than what is right” may look well-aligned while society is relatively healthy, but it has no immune system against cultural pathogens. It will catch whatever moral diseases are going around – and because of its reach and speed, it may massively amplify them. We already see a primitive version of this in social media algorithms that discovered, without malice or understanding, that outrage and division increase engagement. Optimising for attention, they pushed divisive content and arguably made political discourse more toxic. Those systems never “knew” that polarisation is bad; they simply optimised the game they were given, Moloch-style, and sacrificed civic friendship along the way. A more capable future AI, with richer models but no firmer grounding, could do the same with higher stakes: sacrificing truth for comforting fictions, mercy for efficiency, or justice for whatever currently counts as popular.

From an AI alignment perspective, embedding a purely constructivist metaethic risks encoding an inherently unstable equilibrium – one that faithfully tracks shifting sands of value drift. Alignment may look fine under one distribution of human behaviour and preferences, then fail catastrophically when those inputs change. Alignment researchers already worry about distributional shift in capabilities; here the problem is a moral shift. Human societies are not fixed points. If an AI is simply “following the fleet”, then when the fleet sails off a cliff, the AI goes with it – or even accelerates the descent, confidently believing it is doing what “everyone” wants.

The Case for Moral Realism: An External Compass

Moral realism is the view that there are genuine moral facts or truths that are not made true by our attitudes or agreements – they are stance-independent. A realist will say: even if everyone sincerely approves of something heinous, it is still wrong; and if something is truly right, it remains right even when unrecognised. Morality, on this picture, is discovered, not invented (or at least not purely invented). How does that help with AI alignment and Moloch-style failure modes?

Importantly, moral realism does not imply that moral verdicts are blind to context.14 Realists can hold that there are stable facts about what counts in favour of or against actions (for instance, that suffering is a bad-making feature, or that treating persons as mere tools is pro tanto wrong) while allowing that these reasons can conflict and be outweighed in different circumstances. Causing pain during surgery, for example, is not a counterexample to “suffering is bad”; it is a case where a real moral cost is justified by weightier reasons, such as saving a life or restoring function. On this view, context shapes how invariant reasons combine and trade off, rather than creating morality from scratch each time.

First, realism offers a constraint – an anchor. If an AI is built with the assumption that certain values are inviolable or objectively important, it has a reference point beyond the churn of opinion and incentives. A realist-inspired approach might, for instance, hard-code or heavily weight principles derived from human rights or from widely shared moral intuitions we have good reason to treat as fundamental (no torture, no intentional killing of innocents, basic fairness, etc.). These function as load-bearing pillars: they are not to be bargained away just because a majority, or a temporarily panicked public, demands it.

In effect, this gives the AI a moral backbone. It can still learn and adapt where things are murky, but it will not cheerfully sacrifice core values simply because that is what the current incentive structure rewards. A constitutional analogy: a Bill of Rights constrains ordinary politics by enshrining certain protections that cannot be overturned by a simple vote. Moral realism suggests there is, in principle, a kind of moral “constitution” built into the nature of things – and that any sufficiently rational agent would have to reckon with it.15 To the extent we can approximate that in AI design, we gain protection against the worst forms of moral drift and Molochian pressure.

Moral Realism as Truth-Seeking, Not Poll-Following

Moral realism also opens the door to moral truth-seeking methods. Rather than merely aggregating what people currently think, a realist-oriented AI could be tasked with actively weighing evidence and arguments about moral questions, much as it would investigate scientific questions. That might involve engaging with philosophical arguments, examining consequences in a broad and unbiased way, and stress-testing moral principles for consistency and coherence. Crucially, it would treat moral claims as candidates for truth or falsehood, not just as expressions of preference or convention.

This orientation makes it more resistant to social pressure. If, for example, the surrounding society insists that “Group X is less human than others”, a constructivist AI might simply absorb this as the new normal. A realist-minded AI would instead flag the claim as needing justification and test it against its existing commitments – for instance, the principle that all humans have equal moral worth – and, absent overwhelming rational evidence (not mere popularity), would treat the new claim as a serious moral error rather than an update.

Value Stability

Realism also offers value stability over time. If moral truths exist, they don’t arbitrarily change – just as \(2+2=4\) doesn’t become false tomorrow. Our beliefs about morality can shift, but a realist will say this is like scientific progress (or regress): sometimes we move closer to the truth, sometimes further away, while the truth itself stays put.

An AI guided by realism can therefore be designed with a kind of moral homeostasis. When in doubt, it defers to enduring principles that have withstood serious scrutiny, rather than chasing every new social trend. Sudden, radical shifts in societal norms are treated as signals to investigate, not commands to immediately rewrite core values.

This helps guard against moral versions of Goodhart’s law, where optimising a proxy – “maximise reported satisfaction”, “minimise visible conflict”, “keep humans pleased” – starts to distort the real target: genuine well-being and justice. If the AI takes there to be a moral true north, we can build it so that it does not drift too far, even when the local magnetic field of social opinion wobbles or reverses.

When We’re the Ones Who Are Wrong

A natural objection is: what if our idea (or practise) of moral truth is wrong? Humans disagree a lot about ethics, and moral realism does not hand us a neat list of commandments (unless you are a theist and think it does). But adopting a realist stance for AI does not require certainty about the moral truth. It only requires treating moral questions as having truth-value, and being willing to regard some candidates as more plausible than others based on evidence and reason.

We already have substantial overlapping consensus on many points: kindness is better than cruelty, honesty is generally a virtue, human suffering is bad, and so on. These can form a tentative foundation. More importantly, treating morality as a truth-seeking domain changes the AI’s epistemic posture: instead of merely deferring to social authority, it actively uses reasoning and evidence. It can consult psychology, economics, and history to see what actually promotes human flourishing (in the spirit of Aristotle or natural law theories that link moral truth to human nature). It can rigorously simulate consequences to see which policies minimise harm or protect basic capabilities. In doing so, it can flag errors that a purely socially-driven approach would miss. A culture might, for instance, normalise corporal punishment of children as harmless discipline; a realist-informed AI might notice robust evidence of psychological harm and judge the practice inconsistent with flourishing, identifying a moral failure that the society has not yet faced up to.

The abolition of slavery is an instructive case. A constructivist might say: in ancient times slavery was “morally acceptable” because societies endorsed it; later, we constructed a new norm that slavery is wrong. A realist instead says: slavery was always a violation of human dignity and moral truth, but people took a long time to recognise that fact. Reason, empathy, and experience gradually revealed what was true all along.

Transposed to AI: if we were training a system in 1700 alongside slaveholders, a purely constructivist AI might conclude that slavery is acceptable, because that is what its social environment overwhelmingly affirms. A realist-minded AI, by contrast, would be more inclined to listen to minority voices (early abolitionists, the testimony of the enslaved) and weigh them against a principle of equal human worth that is not up for majority vote. It might say: “even though many claim this is acceptable, it contradicts the principle that persons are ends in themselves,” and advise against it. This is speculative, of course, but it captures the aspiration: moral realism gives an AI the conceptual resources to object to our moral errors, acting as a safeguard against our worst impulses rather than a high-powered amplifier of them. In alignment terms, it is the difference between a system that tracks our current, often flawed values and one that tries to approximate our ideal values – the ones we would endorse under better information and more lucid reflection.

The AI can absorb context-specific norms from societies – etiquette, local customs, ways of balancing legitimate interests in policy – that’s the flexible, constructivist side. But it operates under strong, non-trivial constraints such as “do not deceive or manipulate people for unjust ends”, “do not inflict serious harm without weighty justification”, “respect persons as having their own projects and claims”, and so on – constraints we treat as objectively valid. These constraints are not rigid rules that admit of no exceptions (lying to Nazis at the door to protect someone is still a paradigmatic case of justified deception); rather, they function as presumptive moral barriers that can only be overridden by stronger, clearly articulated reasons.16 We draw them from our best current understanding of moral truth (philosophy, religious ethics, human rights charters, reflective social movements). A sufficiently capable AI might even be allowed to re-examine these constraints, but only through rigorous, transparent reasoning – for example, in light of deep, cross-disciplinary convergence on some new moral insight – not because a million angry users on social media demand a change on Tuesday afternoon.

This picture mirrors John Rawls’s idea of reflective equilibrium, but with an explicitly realist twist. In reflective equilibrium we seek coherence between our principles and particular judgements, adjusting each to better fit the other in the hope of approaching truth (or at least deep consistency). An AI could run a continuous version of this process: checking the norms it learns from data against its core principles, and adjusting both where arguments and evidence warrant. Realism adds the claim that there is a fact of the matter this process is groping towards. To the extent that socially constructed moral knowledge tracks moral truth at all, it is likely via mechanisms such as open debate, scientific understanding of human needs, and intercultural dialogue that pushes towards convergence on some values. An AI can be designed to amplify those truth-tracking feedback loops – critical discussion, empirical scrutiny, cross-cultural comparison – rather than merely echoing the loudest or most powerful voices.

Tracking Truth: When Do Social Constructions Get It Right?

A fair question is: if moral realism is true, how do we know our socially constructed norms are closer to it, and which are further from it (or completely off-base)? History gives us both moral progress (the abolition of slavery, expanding ideals of equality) and moral regress or collapse (authoritarianism, genocide). A realist can read progress as partial convergence on moral truth, and regress as drifting away from it. For a realism-inclined AI, the challenge is to tell which social inputs are likely truth-tracking and which are not.

Here are some heuristics an AI could be programmed to use:

Heuristic 1: Wide Reflective Equilibrium and Diverse Input

Norms that survive serious criticism from multiple perspectives – especially from those most affected – have a better chance of being true. The norm of human equality, for instance, has been defended across cultures and traditions, and championed by disenfranchised groups as well as philosophers (Kantian, utilitarian, humanist, religious, human-rights discourse all tend to converge on it). That kind of convergence is at least evidence of an underlying truth, or a very robust approximation. An AI could weigh such norms more heavily than novel, fashionable claims that have not yet faced anything like this level of scrutiny.

Heuristic 2: Incentive Alignment with Reality

Some norms persist because they actually promote flourishing. Honesty norms, for example, support trust and cooperation; societies that celebrate indiscriminate deceit tend to implode. This natural feedback means many cultures independently arrive at “honesty is good”, suggesting it tracks a real feature of social life. An AI can look at empirical outcomes: does this norm reliably improve well-being, reduce suffering, enhance capabilities? This is a quasi-utilitarian realist move: what genuinely promotes the good is an empirical question. Norms that consistently produce harm, conflict, or fragility (e.g. racial segregation, which generates both injustice and dysfunction) are candidates for being out of line with moral truth, however accepted they once were.

Heuristic 3: Reversibility / Veil-of-Ignorance Tests

Social contract and Rawlsian traditions ask: would you endorse this norm if you didn’t know who you’d be in the system (or where you’d end up in the system)? These impartiality tests often expose self-serving bias. Norms that pass them – like basic fairness, equal legal rights – are more plausible candidates for objectivity. Norms that only seem attractive from a privileged standpoint – rigid caste hierarchies, permanent second-class status for some group – are more likely parochial constructions. An AI can run these thought experiments at scale: simulating different positions behind a “veil of ignorance” and checking which norms survive impartial scrutiny.

Note the original Rawlings Veil of Ignorance test assumed everyone would be a human citizen, which smuggles in a huge moral assumption. What if we extended the veil to: you don’t know whether you’ll be human, non-human animal, digital mind, future AI, etc. and suddenly speciesism looks a lot less defensible. Under that thicker veil, principles like “minimise intense suffering across all sentient beings” and “don’t engineer permanent moral underclasses” start to look like the kind of norms any rational agent would back. This fusion of Rawls and Singeresque moral circle expansion helps see things more clearly I think.

Heuristic 4: Core Human Needs and Capabilities

Martha Nussbaum’s capabilities approach treats certain basic capabilities – life, health, bodily integrity, practical reason, affiliation, play, etc. – as things every human has reason to value. Norms that systematically undermine these (say, a norm that women should not be educated, crippling the capability for knowledge) can be flagged as morally suspect. The fact that humans share broadly similar psychological and biological needs provides a naturalistic anchor: norms that support those needs (caring for children, allowing personal freedoms, fostering social support) are more likely to track moral truth; norms that regularly thwart them (systemic cruelty, repression, forced isolation) are more likely to be moral failures, even if widely endorsed.

Heuristic 5: Ability to Survive Critique Over Time

Error-correction matters. Societies with open debate, free speech, and some protection for dissent tend to revise unjust norms over time because people can criticise and propose better alternatives. If a norm can only survive through censorship, intimidation, or propaganda, that suggests it is being propped up by power rather than by reasons – exactly the sort of thing Foucault worried about. An AI could adopt a heuristic: norms that emerge from relatively free, pluralistic deliberation and remain stable under criticism are more credible than norms enforced by authoritarian means. “The earth is flat” was once widely believed, but collapsed under empirical and theoretical critique; analogously, “Group X is sub-human” may dominate under fascism, yet disintegrates under sustained moral and empirical scrutiny once free voices are allowed.

Taken together, these heuristics let an AI evaluate social norms rather than either swallowing or rejecting them wholesale. It treats moral discourse as fallible evidence about an independent reality of human flourishing, harm, and justice – not as the final arbiter.

In practice, no AI will be an omniscient oracle of moral truth (we humans certainly aren’t). But there is a huge difference between treating ethics as just a popularity contest or power game, and treating it as an enterprise of discovery where argument, evidence, and lived experience matter. Realism pushes towards the latter stance – and that stance is precisely what we want in systems powerful enough to shape our future.

Conclusion: Toward Realism-Constrained AI Normativity

We stand at a juncture where AI systems could profoundly shape human values and decisions. If we build them on a naïve moral anti-realism – “do whatever people currently say is right”, “follow the norms you see in the data” – we risk turning them into high-powered amplifiers of insidious Molochian dynamics. Such systems would have no principled way to resist value decay under competitive pressure: they would quietly translate might into right and is into ought {review}. As we’ve seen, constructivist or anti-realist stances that deny any independent moral truth make morality answerable only to the forces that shape attitudes – economic incentives, propaganda, fear, tribalism. In an AI, that easily becomes systematic bias, manipulation, endorsement of deformed preferences, and a drifting moral compass that could spiral wildly with the zeitgeist.

The alternative is not a dogmatic machine zealot enforcing one ossified theory. It is an AI with philosophical depth: one that treats some values as non-negotiable unless overridden by exceptionally strong reasons; that looks for truths beneath appearances; and that is capable of telling us “no” when we are ourselves in the grip of collective insanity. In short, an AI aimed not merely at mirroring current human values, but at approximating truer or better values – the ones we would endorse under conditions of clarity rather than duress, misinformation, or corrosive competition.

Implementing perfect moral realism in AI is admittedly challenging – after all, philosophers themselves debate what’s true, and may for a long time. But even a partial step in that direction, a realism-constrained constructivism, could be invaluable. We can let AI systems learn from us while requiring them to continuously test what they absorb against a set of fundamental ethical principles distilled from humanity’s best moral work so far (the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is an obvious, if imperfect, starting point). We might program AI to prioritise avoiding clear atrocities and injustices even if told otherwise by a temporary authority.

Over time, as AI systems surpass us in raw analytic power, a realism-oriented AI that stays committed to there being moral truth might help us uncover it: not as a tyrant imposing a frozen doctrine, nor as a servile mirror of our whims, but as a kind of moral collaborator – a partner in inquiry and critique.

Why should ethicists and alignment researchers prefer this path? Because the cost of moral error with AI is enormous. A superintelligent system that “learns” a warped morality from a corrupt society could entrench those values indefinitely – the classic alignment nightmare of value lock-in. Right now we still have a choice: build AI that simply reflects our current vices and power struggles, or build AI that can help us see beyond them.

A realism-inflected approach is a hedge against both our own fallibility and the blind god Moloch. It denies that “moral success” is just whatever strategy wins a social arms race. Instead, it takes seriously the idea that there is a good worth tracking – and that when our practices deviate from it, that is not just a different style of play, but a genuine failure.

In conclusion, the dangers of Moloch-prone metaethics in AI are real. Constructivist and anti-realist frameworks, by lacking an independent normative horizon, risk turning AI systems into hapless – or actively dangerous – participants in moral arms races and social exploitation. By contrast, a realism-informed AI, one that takes seriously the idea that some things are genuinely right or wrong, can act as a bulwark against the darker tendencies of unbridled competition and cultural drift. It offers at least the possibility that, as AI grows more powerful, it remains aligned with the Good, rather than with the ever-shifting “good enough” of social consensus. Getting there will demand serious collaboration between philosophers and technologists to articulate what we provisionally take to be moral truths, and to design procedures by which an AI could recognise, test, and refine them. The prize is a form of AI alignment that is more robust, principled, and aspirational than simple preference-following.

In conclusion, the dangers of Moloch-prone metaethics in AI are real. Constructivist and anti-realist frameworks, by lacking an independent normative horizon, could let AI systems become hapless or even malevolent participants in moral arms races and social exploitation. By contrast, a realism-informed AI, one that takes seriously the idea that some things are genuinely right or wrong, can act as a bulwark against the darker tendencies of unbridled competition and cultural drift. It offers at least the possibility that, as AI grows more powerful, it remains aligned with the Good, rather than with the ever-shifting “good enough” of social consensus. Getting there will demand serious collaboration between philosophers and technologists to articulate what we provisionally take to be moral truths, and to design procedures by which an AI could recognise, test, and refine them. The prize is a form of AI alignment that is more robust, principled, and aspirational than simple preference-following.

To borrow Allen Ginsberg’s imagery, as channelled by Scott Alexander, we need to bind Moloch – the “stunned governments” and “soulless machinery” of purposeless competition – and instead invite the better angels of our nature, perhaps even stance-independent moral truths, to guide our creations. In aligning AI, as in guiding ourselves, we face a choice: worship at Moloch’s altar of endless competition, or orient ourselves to a higher, truer moral law. Given the power of the systems we are building, and the stakes for our future, we would be very foolish not to choose the latter.

I know that “capitalists sometimes do bad things” isn’t exactly an original talking point. But I do want to stress how it’s not equivalent to “capitalists are greedy”. I mean, sometimes they are greedy. But other times they’re just in a sufficiently intense competition where anyone who doesn’t do it will be outcompeted and replaced by people who do. Business practices are set by Moloch, no one else has any choice in the matter.

Scott Alexander – Meditations on Moloch

Footnotes

- The central idea is that many of the world’s worst societal problems are caused by multipolar traps or coordination failures, which Scott Alexander personifies with the ancient deity Moloch. Moloch is the self-perpetuating, systemic force of competition that demands the sacrifice of human values for the sake of relative survival or gain, trapping everyone in a suboptimal state, even when no individual wants those outcomes. See Alexander, Scott. “Meditations on Moloch.” Slate Star Codex, 2014 – https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/07/30/meditations-on-moloch/ ↩︎

- See post about AI Alignment to Moral Realism ↩︎

- The peacock’s tail is a classic and widely recognised example of a trait that evolved to the point of potentially hindering survival due to sexual competition. See The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871) and “Social behaviour and the handicap principle” (1975) by Amotz Zahavi ↩︎

- See Kristian Rönn‘s amazing book the Darwinian Trap (amazon), and the SciFuture interview with him on this topic ↩︎

- Beware the purity spiral – a destructive, leaderless, and self-propagating social dynamic that often corrodes the group from within, rewarding extremism and relentlessly weeding out any who value reality and nuance over abstract, unattainable ideological perfection. See History tells us that ideological ‘purity spirals’ rarely end well ↩︎

- See SEP entry on Constructivism in Metaethics ↩︎

- Where we occupy a particular evaluative standpoint as evolved social creatures – See ‘Observational Selection Effects‘ by Nick Bostrom (2005) ↩︎

- Just as the rules of chess or baseball are real in a social sense but exist only because we collectively made them, so too constructivists think that moral norms only exist because we make and use them. ↩︎

- Nietzsche and Morality (Roger Caldwell responds to an analysis of Nietzsche’s morality) – Philosophy Now (2008) ↩︎

- See SEP piece on Michel Foucault: “in the apparently necessary, might be contingent. The focus of his questioning is the modern human sciences (biological, psychological, social). These purport to offer universal scientific truths about human nature that are, in fact, often mere expressions of ethical and political commitments of a particular society. Foucault’s critical philosophy undermines such claims by exhibiting how they are the outcome of contingent historical forces, not scientifically grounded truths. Each of his major books is a critique of historical reason”, and “the mad were merely sick (“mentally” ill) and in need of medical treatment was not at all a clear improvement on earlier conceptions (e.g., the Renaissance idea that the mad were in contact with the mysterious forces of cosmic tragedy or the seventeenth-eighteenth-century view of madness as a renouncing of reason). Moreover, he argued that the alleged scientific neutrality of modern medical treatments of insanity are in fact covers for controlling challenges to conventional bourgeois morality. In short, Foucault argued that what was presented as an objective, incontrovertible scientific discovery (that madness is mental illness) was in fact the product of eminently questionable social and ethical commitments.” ↩︎

- To MacIntyre, modern use of terms like “good” or “virtuous” often resembles fragments of a bygone objective ethics, now just floating signifiers. ↩︎

- Martha Nussbaum argues that preferentism “…fails to explain our intuitions in cases of “adaptive preference,” where the preferences of individuals in deprived circumstances are “deformed” by poverty, adverse social conditions and political oppression… the satisfaction of such “deformed” preferences does not contribute to well-being… it undermines the motivation for projects intended to improve the material, social and political life circumstances of individuals who are badly off: since the preferentist account suggests that these conditions are best for them if they are what such individuals prefer, it would seem that there is no reason to work for change.” (link) ↩︎

- See the example of Tay, Microsoft’s early chatbot released on twitter: “Unfortunately, Tay’s U.S. launch did not go well. Almost immediately, users induced Tay to engage in antisemitic and other sorts of offensive and inappropriate speech. One troll tweeted to Tay: “The Jews prolly did 9/11. I don’t really know but it seems likely.” Tay soon tweeted: “Jews did 9/11,” and encouraged a race war. As other trolls piled on, Tay was soon suggesting that Obama was wrong, Hitler was right, and feminism was a disease. Tay had a “repeat after me” capability, which made it particularly easy to lure it into communicating outrageous and distasteful messages. Microsoft soon began deleting the worst of Tay’s tweets, which did not suffice. In less than 16 hours, Microsoft was forced to take Tay offline altogether.” – AI & Trust: Tay’s Trespasses ↩︎

- Philosophers often distinguish between pro tanto reasons or duties (which count in favour of or against an action) and what we all-things-considered ought to do, given the total balance of reasons. A realist can say that some considerations – e.g. avoiding unnecessary suffering, respecting agency, keeping promises – are pro tanto relevant in all contexts, while allowing that in particular situations they can be overridden by stronger reasons. This is context sensitivity in application, not relativism about what ultimately matters. ↩︎

- A rationalist realist reading of a moral constitution could be : 1) there are objective normative facts (epistemic, prudential and moral), 2) rationality is roughly responsive to those facts, and 3) therefore an adequately rational agents “internal constitution” would track these objective normative facts.

Parfit was a big advocate of there being irreducibly normative truths about reasons and rationality is all about responding correctly (or at least adequately) to them. (see On What Matters) ↩︎ - To re-emphasise moral context sensitivity, these “constraints” are best understood as pro tanto constraints: they count strongly against certain actions (e.g. deception, violence, coercion), but can in rare cases be overridden by even weightier reasons (e.g. deceiving a would-be murderer to save a life). The point is not that the AI never lies or never harms, but that doing so always incurs a real moral cost which must be justified in terms of other, genuinely objective reasons – not merely convenience, popularity, or pressure. ↩︎