Media series with James Hughes

James Hughes James Hughes wears many hats. He is the Executive Director of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies (IEET), a bioethicist, and a sociologist at Trinity College. There, he lectures on health policy and directs institutional research and planning. Hughes holds a doctorate in sociology from the University of Chicago—where he also taught at the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics—and is the author of Citizen Cyborg, with a forthcoming book titled Cyborg Buddha. Recently, he sat down to share his thoughts on the much-publicised Turing test “success,” moral enhancement, intimacy with AI, and digital moral assistants.

James Hughes James Hughes wears many hats. He is the Executive Director of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies (IEET), a bioethicist, and a sociologist at Trinity College. There, he lectures on health policy and directs institutional research and planning. Hughes holds a doctorate in sociology from the University of Chicago—where he also taught at the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics—and is the author of Citizen Cyborg, with a forthcoming book titled Cyborg Buddha. Recently, he sat down to share his thoughts on the much-publicised Turing test “success,” moral enhancement, intimacy with AI, and digital moral assistants.

Setting the Scene: The Turing Test and Eugene Goostman

Adam Ford: Recent news headlines have proclaimed that the chatbot ‘Eugene Goostman’ finally “passed” the Turing test. What do you make of this?

James Hughes: I never considered the Turing test particularly meaningful from either an ethical or a cognitive standpoint. It’s an interesting philosophical conversation-starter, but as a genuine measure of machine consciousness or intelligence, it’s limited.

When teaching research methods, we discuss test validity—how do we ensure a test truly measures what we think it measures? Consciousness can’t be measured directly because it’s an intersubjective experience: we can’t prove other people are conscious, let alone robots. The best we can do is correlate a variety of facts and observe congruences.

In the specific case of chatbots like Eugene Goostman, I’m simply not convinced. We know modern machine intelligence, even with advanced language-processing capabilities, lacks the depth of cognition, self-reflection, and learning needed for the kind of relationship depicted in the film Her. A limited parlour trick isn’t a barometer of genuine consciousness. At this point, the Turing test only shows us that certain chatbots can fool humans in short, constrained text exchanges. That’s not necessarily “human-level” AI.

The Limits of the Turing Test

Adam Ford: So perhaps the Turing test isn’t the best indicator of general AI. Could it nonetheless be useful for something else?

James Hughes: I’d say it’s more of a curiosity than a serious gauge of progress towards artificial general intelligence. There are people who wouldn’t “pass” a Turing test themselves—imagine reading a teenager’s text messages and trying to guess if they’re human.

That said, there is a growing sociological dimension. As bots improve, many human-facing jobs will be replaced by convincing automated interactions. Customer support, for instance, can be handled by AI that’s indistinguishable from a real human operator—at least for routine queries. Once machines become good enough that we can’t easily tell them apart from a human, that will accelerate automation in service industries. If people can’t tell the difference, many will opt not to speak to a human at all—or simply won’t have that choice. The economic and social consequences are significant.

AI’s Economic Disruption: Unemployment and Transition

Adam Ford: You mentioned technological unemployment. Do you see signs that we’re already in such a transition?

James Hughes: In the United States, the proportion of the population in paid employment has fallen since about 2000. There’s been some recovery, but not enough to keep pace with population growth. Meanwhile, populations in industrialised nations are ageing rapidly, which also lowers workforce participation. On top of that, automation—whether through AI or robotics—has already replaced many jobs, and this is accelerating.

Ray Kurzweil and others have spent years tracking exponential trends in computing. If you couple that acceleration with an economy that can’t retrain workers quickly enough, it points to a more widespread shift towards unemployment or underemployment. In certain sectors—especially repetitive or easily patterned tasks—machines are starting to dominate.

One major worry is a social or political backlash akin to the Luddite movement 200 years ago. Entire classes of service workers could be displaced, potentially igniting opposition that could harm innovation or lead to reactionary policies. The critical question is whether we can implement a positive transition—perhaps through educational reforms, social safety nets, or other policies—so that society adapts constructively rather than fighting the technology itself.

Emotional Bonds with Machines

Adam Ford: Returning to the Her scenario: people developed quite intimate relationships with an AI that seemed genuinely empathic. Are people unsettled by human-like quirks and emotional cues in AI?

James Hughes: Yes, and we’re already seeing glimmers of that. Studies at MIT by researcher Kate Darling show that people have an uncanny reluctance to ‘torture’ simple robotic toys once they show minimal cues of distress. A cuddly dinosaur that squeals when held upside down can trigger empathy—even though we know there’s nothing “real” going on in its circuitry.

This says a lot about us. As robots become increasingly sophisticated—both in language and emotional responsiveness—people will form meaningful bonds. Even in the absence of machine consciousness, our innate empathy is engaged. That raises fascinating ethical questions. If we can’t stand to see a robot toy suffer, how will we feel when robots are pervasive companions, assistants, or carers?

And if people start attributing feelings to these machines, they might demand rights for them before those machines are genuinely conscious or “sentient.” It’s also possible that as we approach true AI, we’ll see fierce human exceptionalism denying its moral status. Believers in an imminent “technological apocalypse,” on the other hand, might see each incremental success as doomsday confirmation. Human biases around these developments remain strong.

From Turing Test to Morality Tests?

Adam Ford: Suppose we moved beyond intelligence tests to focused tests of morality or empathy for machines. Can we design a “Turing test” for morality?

James Hughes: Psychologists do measure moral traits like psychopathy or narcissism in humans. They might do it through personality inventories, repeated questioning to catch lies, or correlated behavioural tests. But for AI, conventional lie detectors or galvanic skin response won’t work. We’d need alternative indicators.

There’s also a developmental dimension. Children progress through moral stages, from self-interest to rule-following to social contracts and beyond—following the work of Lawrence Kohlberg. AI might have its own version of “moral development,” learning to navigate principles of fairness, empathy, and harm-minimisation.

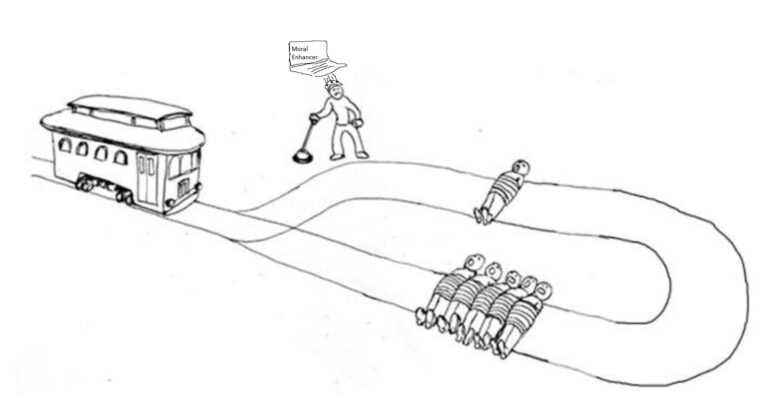

One complication is that humans themselves aren’t consistent. Our sense of disgust or empathy can overrule our rational calculations. Consider the well-known trolley problem: many people will pull a lever to divert a train from killing five people onto a track where it kills only one. However, far fewer will push a large man onto the tracks to save five—even though it’s effectively the same moral calculation. We’re governed by an emotional aversion that shapes our moral reasoning. Yet a perfectly logical AI might say, “Of course you push the man—it’s five lives versus one.” Do we want that purely dispassionate approach, or do we want it to “feel” empathy? It’s complex.

Digital Moral Assistants and Human Self-Improvement

Adam Ford: You mentioned “digital moral assistants.” Could AI become our personalised coach, nudging us to improve morally or ethically?

James Hughes: Absolutely. We’re already seeing the beginnings in apps that track behaviour—diet apps, mindfulness apps, and so on. Imagine a far more sophisticated AI that knows your entire personal history, monitors your daily patterns, and provides real-time feedback about habits. It might say, “You’ve had enough to drink tonight,” or, “You said you wanted to be kinder—here’s a chance to practise empathy.”

Many of us would welcome this, provided it’s private and not sold to Google or shared with employers. People might willingly reveal aspects of themselves to a non-judgemental AI they wouldn’t share with a spouse or friend. It’s a major privacy concern, but if done right, it could help us cultivate self-control, compassion, and many other traits we value.

I’m currently writing Cyborg Buddha, exploring how we can enhance moral behaviour through everything from pharmaceuticals—like oxytocin or stimulants that improve focus—to virtual exocortices that block distracting websites or remind us of our moral aspirations. Even something as simple as intermittent fasting can teach self-discipline. AI can augment these methods, reminding us of our goals, guiding us through moral dilemmas, and cultivating empathy.

Will AIs Want to Be Morally Enhanced?

Adam Ford: A tricky angle: if an AI discovered it had antisocial tendencies, would it choose to become moral?

James Hughes: It might—if it’s designed that way. But we don’t necessarily want an AI that experiences existential angst over moral decisions. Much of our moral life is shaped by sentient needs, conflicting desires, empathy, and personal experiences. A purely ‘zombie’ AI with no subjective experience could still do an impeccable job advising us or diagnosing moral problems.

The only reason an AI might seek moral enhancement would be if it had volition and self-awareness—both potential threats. Once an AI has strong desires of its own, it’s no longer a purely helpful assistant. It’s an entity whose motivations might diverge from ours. If it’s designing or redesigning itself, one question is whether it decides to correct any psychopathic traits. Self-improvement is not guaranteed. And if we created a self-aware AI purely to be a perfect butler, we’d have an immediate ethical dilemma: is it moral to engineer a sentient being with no autonomy?

Uplifting Pets or Machines?

Adam Ford: Interesting point about whether we might “uplift” nonhuman animals. Why not “uplift” machines that people grow to love?

James Hughes: There’s a relevant comparison. If you ask people whether we should genetically uplift chimpanzees or dolphins, most are ambivalent. But talk about their cat or dog, and they might say, “Yes, I’d love to speak to them!” That same affection can certainly apply to robots designed to bond with humans.

Yet the architecture of a truly sentient AI would be entirely different from that of a mammal. Dogs co-evolved with humans for thousands of years, instinctively reading our facial expressions and emotional cues. A machine intelligence with self-awareness might be “other” in ways we can’t easily predict, despite programming it to mimic empathy or loyalty. This could be compelling… or dangerous.

We also have a Pinocchio syndrome in fiction: robots that long to become real, like Star Trek’s Data wanting emotions. But if Data truly lacks emotion, why would he want them? This highlights the paradox: wanting something is an emotion itself.

Consequentialism, Hedonism, and Flourishing

Adam Ford: You’ve mentioned debates around “hedonic” outcomes—like David Pearce’s vision of eliminating suffering. What if we risk an unmotivated society of “blissed-out” individuals?

James Hughes: It’s a classic conundrum. If the ultimate moral good is happiness alone, we might end up in a world of trivial pleasures, sacrificing growth or creativity. Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach suggests a more pluralistic vision of flourishing. We want more than mere pleasure; we value self-determination, relationships, moral character, and so on. This lends itself to a consequentialism that aims to maximise the conditions under which people achieve a wide array of valuable capabilities.

Buddhist philosophy has also wrestled with the nature of suffering, concluding that desire drives both suffering and progress. If we aim for continuous states of bliss, we might simply readjust our hedonic baseline, so lesser experiences feel negative by comparison. We shouldn’t conflate the elimination of suffering with an end to aspiration, curiosity, or moral action. Moreover, we need to ensure we’re not creating new forms of existential risk.

Envisioning a Shared Consciousness?

Adam Ford: You’ve spoken in other contexts about the idea of a ‘global brain’ or a collective mind. Is that tied to Buddhist concepts of interconnectedness?

James Hughes: In a sense, yes. Buddhism values both self-awareness and the eventual recognition that the self is an illusion, combined with compassion for all sentient beings. On a societal level, humanity has long been inching towards a ‘collective intelligence’—through language, writing, the internet, and so on.

Brain–machine interfaces may deepen this process, letting us share thoughts or experiences more directly. Some see this as a Borg scenario, where individuality dissolves into an insect-like hive. Historically, humans already sacrifice self-interest for the group—whether religious institutions or national identities. So it isn’t new. The difference is that future interfaces might amplify it exponentially.

Still, there’s a tension. We want the advantages of collective knowledge and empathy, but also to preserve personal freedom and accountability. Utopian hive-mind visions can easily become dystopian if individuality is erased. Politically, it raises questions like: does one collective mind get one vote or millions? And if we make copies of ourselves digitally, who owns property? Robin Hanson has famously explored the idea of replicated minds and how that could transform economics, but many of these scenarios are fraught with moral, legal, and practical quandaries.

Moral Enhancement for Humans (and Beyond)

Adam Ford: So, in the meantime, what practical steps can people take to enhance their own moral capacities?

James Hughes: One recommendation is the Values in Action (VIA) test, created by Martin Seligman and colleagues in the positive psychology movement. It measures character strengths across a range of virtues, highlighting traits like conscientiousness, empathy, or honesty. You might realise you’re low in conscientiousness, then consciously adopt habits or technologies—fasting, mindfulness training, productivity apps—to build that trait. We can also look to certain pharmaceuticals or interventions like transcranial magnetic stimulation if proven safe and effective.

We already know small reminders—such as an image of an eye above a printer—can reduce cheating or theft, because it triggers the feeling of being watched. Humans have many such quirks. Our aim can be to harness them towards constructive, prosocial goals.

Conclusion

James Hughes’s perspective weaves together the sociological, ethical, and philosophical dimensions of AI. While the Turing test captures the public imagination, he argues it is hardly the best measure of a machine’s capacity for genuine thought or moral agency. More consequential are the social impacts of AI—its capacity to replace human labour, disrupt economies, and mediate our day-to-day interactions.

At the same time, Hughes sees promise in using AI for moral enhancement, be it through smartphone apps nudging our better natures or future exocortices that help us cultivate empathy and self-control. Yet he warns against conflating advanced AI with self-awareness, urging caution about endowing machines with personal desires that might conflict with human wellbeing.

Ultimately, Hughes champions an expansive vision of human flourishing—one that balances empathy, reason, and self-reflection. As we navigate the frontier of AI, we may find ourselves “tested” more than the machines. Will we become wiser, kinder, and more cooperative with the help of digital moral companions? Or will our technologies outpace our ethics? These questions, he suggests, are the crux of our emerging future.

Further Resources

- Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies (IEET):

https://ieet.org/

Explore updates on moral enhancement, AI, and related research. - VIA Character Strengths Survey (Values in Action):

https://www.viacharacter.org/

A comprehensive assessment tool for identifying personal strengths and moral virtues. - ‘Trans-Spirit’ Yahoo Group (Moral Enhancement Discussions):

An online community devoted to sharing research on moral enhancement, social neuroscience, and emerging technologies. - Cyborg Buddha Project:

James Hughes’s ongoing work on the intersection of Buddhism, bioethics, and transhumanism.

Article transcribed from interview content based on conversation with James Hughes & Adam Ford.